- 2022-08-17 发布 |

- 37.5 KB |

- 470页

申明敬告: 本站不保证该用户上传的文档完整性,不预览、不比对内容而直接下载产生的反悔问题本站不予受理。

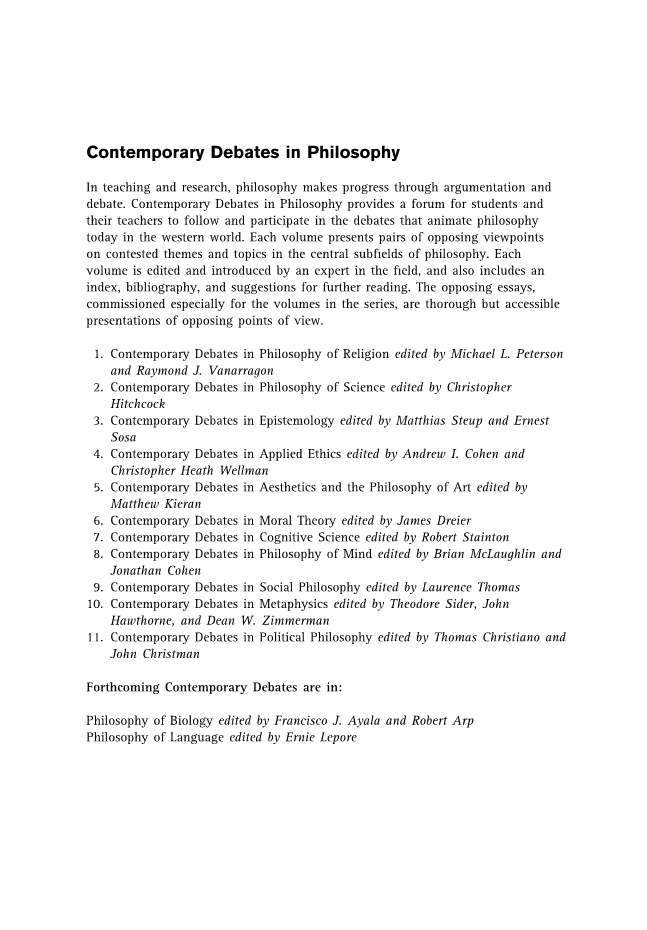

文档介绍

【布莱克威尔当代哲学论争系列】政治哲学